The foundation stone ceremony and Bruno Grimmek’s design

The foundation stone for the memorial center in Plötzensee was ceremoniously laid on September 9, 1951. Once again, the politically charged nature of commemoration in the divided city was clear. The League of Persecutees of the Nazi Regime (BVN) had declared in advance that it would not hold its own ceremony on the date, but asked to hold a speech, as “the largest and most authoritative organization of the former victims.”

The speakers at the foundation stone ceremony were the social affairs senator Otto Bach and the social democrat Ernst Tillich. In the latter’s speech, he not only referred to the resistance between 1933 and 1945, but also appealed to his listeners to fight “neo-fascism and Stalinism.” He called for a “fundamental affirmation of democracy and freedom.” The next day, a West Berliner protested in a letter to the senate, using strong words to condemn an anti-communist bias in Tillich’s speech, in which he saw a “defamation” of the communist resistance against National Socialism.

The League of Persecutees of the Nazi Regime (BVN) had more than 3,000 members and was the largest organization of former victims of National Socialism officially recognized by the West Berlin senate. The BVN had a key influence on many ceremonies held at the former execution site.

In the early 1950s, the league’s actions were clearly marked by the Cold War, and BVN members such as Ernst Tillich expressed stridently anti-communist tones – which did not go unopposed.

The foundation stone was laid by Senator Otto Bach. A sheet of parchment signed by West Berlin’s Mayor Ernst Reuter was bricked in during the ceremony, originally intended to state the number of people executed in Plötzensee for political and religious reasons, arranged by countries of origin.

Although Otto Bach mentioned 2,000 murdered people in his speech, the numbers assumed at this point in time continued to vary significantly. The organizers therefore ultimately decided on a more general message on the parchment

During the years of Hitler’s dictatorship from 1933 to 1945, hundreds of people perished through judicial murder at this place, due to their struggle against the dictatorship, for human rights and political freedom. They included members of all strata of society and almost all nations. Through this memorial site, Berlin honors the millions of victims of the Third Reich who were vilified, mistreated, robbed of their freedom, or murdered due to their political convictions, their religious beliefs, or their racial origins.

Text on the parchment immured during the foundation stone ceremony.

Bruno Grimmek’s design

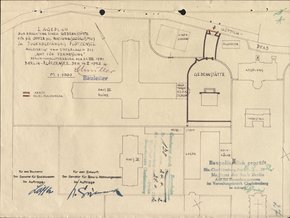

Site map of the memorial center

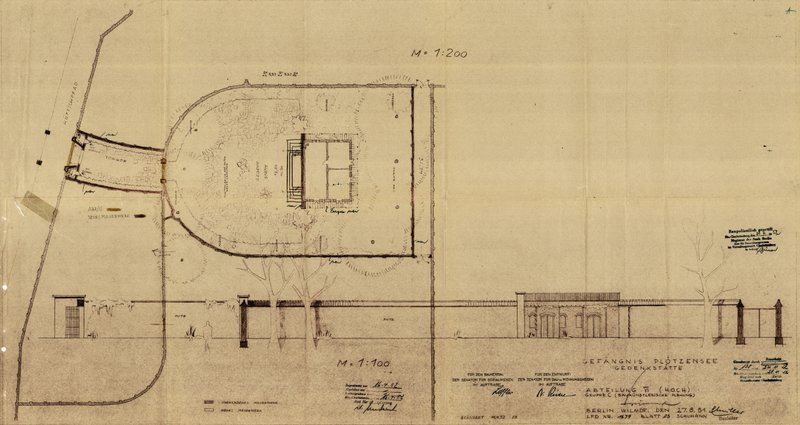

Bruno Grimmek has drawn up initial plans for the memorial center after the first inspection of the grounds of the former execution site in June 1949. He adjusted these plans several times and then submitted a final version at the beginning of 1952.

The site map shows the position of the memorial center within the prison complex.

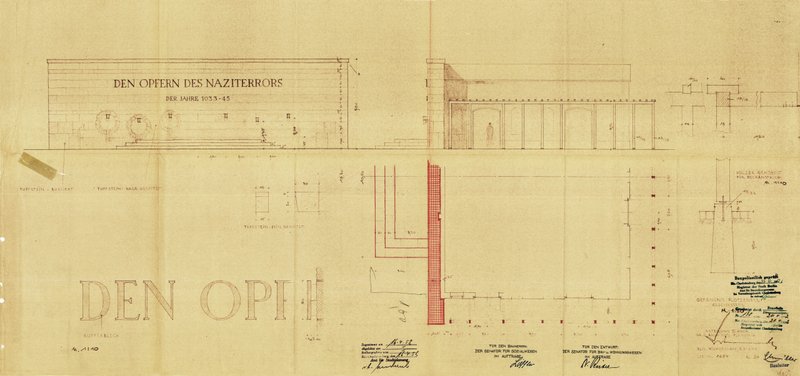

Bruno Grimmek picked up individual elements from the first competition, also dividing the execution shed from a square in front of it using a commemorative wall. Made of tuff masonry, this wall was almost twenty meters long and six meters high, fronted by three steps and concealing the execution shed entirely, in the draft. Five console stones were set into the wall to hold wreaths.

The wall was also to be inscribed in honor of the victims, in metal letters. While the draft version read: “To the victims of the Nazi terror from 1933 to 1945,” the formulation was changed at the end of July 1952 to: “To the victims of the Hitler dictatorship from 1933 to 1945.”

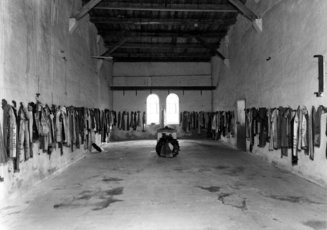

Bruno Grimmek emphasized the execution shed in the overall design to a greater extent than Helmut Heide. After long discussions, it was bordered on three sides by a pergola planted with evergreens, so as to mitigate “the dark character.” The interior space remained unaltered, however, with the steel girder used to hang the victims reinstalled.

The memorial center was accessed, as in Helmut Heide’s design, via Hüttigpfad. Through an entrance portal flanked by two high stone pillars on the opposite side of the street, visitors passed into a slightly curved walled forecourt. This area opened onto the actual memorial center through a second portal.

Parts of the badly damaged House III were demolished, enabling the area of the former execution shed to be separated off from the prison. Grimmek thus created a semi-circular space enclosed by walls, reminiscent of ancient Roman architecture. The commemorative wall and the former execution shed were part of the longitudinal axis.

By separating the memorial center from Plötzensee prison, a publicly accessible space was created, which provided a dignified setting for memorial ceremonies in its large arena.

Bruno Grimmek January 16, 1902 – December 3, 1969

After training as a bricklayer for a year, Bruno Grimmek studied architecture at the construction trades school in Berlin. He subsequently worked in Hans Poelzig’s architecture bureau, among others. In 1927 Bruno Grimmek became chief architect for the city of Gera and then joined the Berlin construction administration department in 1928. During National Socialism, he mainly designed administration buildings under the general building inspector for the Reich capital, Albert Speer.

After the war, Grimmek became head of the design department in the Berlin municipal administration’s construction office, taking over planning for the construction of Plötzensee Memorial Center in this function. In the subsequent years, Bruno Grimmek took part in a large number of national and international architectural competitions. His best-known buildings in West Berlin include the Amerika-Haus, the Palais am Funkturm and the Hansa School.